Sergei Eisenstein — the illustrator. Forgotten side of the influential Soviet film director

Born in the Russian Empire, Sergei Eisenstein marked his name in history with his cinematic works, such as Battleship Potemkin — a silent movie made in 1925.

Despite it being made as a revolutionary propaganda movie, Battleship Potemkin is still considered one of the greatest movies ever made. It continued to receive praises for several generations. Being one of the first film theorists, Eisenstein viewed editing as a powerful tool in the process of film creation. He described a theory of montage in his works, and it was later employed by many worldwide famous filmmakers, such as George Lucas, Brian De Palma, and Woody Allen.

Like many talented artists, filmmaking was just one of Eisenstein’s talents. He was also a talented illustrator who became passionate about this craft from his early days in the Russian Empire. However, Eisenstein’s cinematic works overshadowed all the other ventures and talents he pursued.

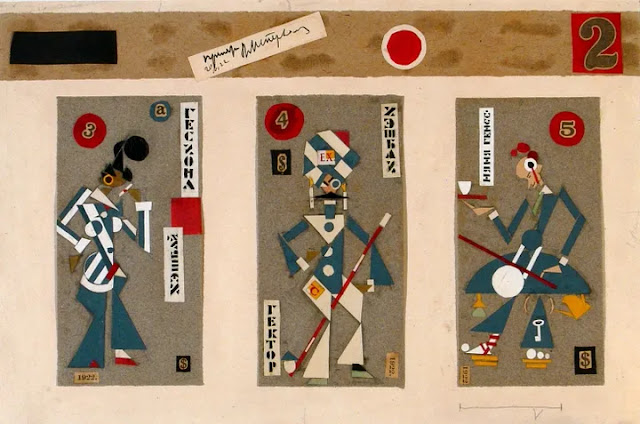

His passion for drawing sketches and illustrations was partially inspired by his father Mikhail, who was a famous architect in the Russian Empire. After the end of the Russian Revolution, Eisenstein found himself working in a theatre as a costume and set designer.

At the same time, his illustrations were published alongside the theatre-themed articles in newspapers and journals. Eisenstein’s theatre illustrations embodied the features of the rising avant-garde art movement — Cubism.

Sketches and illustrations became Eisenstein’s way to express himself as a filmmaker. On paper, he could break all the borders that might have limited his creativity.

%20by%20Sergei%20Eisenstein..webp) |

| Geometrization of the wig (1920) by Sergei Eisenstein. |

Eisenstein’s illustrations became a great tool of communication between the famous film director and the operators, composers, and the make-up artists. From his works, everyone could understand what Eisenstein expects to see on the screen and what music to hear in the background.

Eisenstein was a very passionate illustrator, and his works did include scenes from everyday life in Russia or abstract pieces of art. He created thousands of sketches and illustrations during his lifetime, often creating them on used pieces of paper. Eisenstein’s contemporaries often were given these drawings, and ironically, many did not realize the value those might have had in the future.

%20by%20Sergei%20Eisenstein.webp) |

| The illustration of costume of King Duncan from the Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1921) by Sergei Eisenstein. |

Unfortunately, this led to a loss of a great number of Eisenstein’s sketches and illustrations. His fame was connected with filmmaking and film theory. While there were some attempts to create an exhibition of Eisenstein’s works during his lifetime — it only happened once.

In 1932, some of the works from the period Eisenstein spent in Mexico were exhibited in New York. This exhibition was held without his approval, but he was delighted about the positive review it received in a small column of The New York Times.

The appreciation towards Eisenstein as an illustrator came only a decade after his death. The first major exhibition of his illustrations was held in 1957, in Moscow.

%20by%20Sergei%20Eisenstein.webp) |

| Berlin (1926) by Sergei Eisenstein. |

It featured more than 300 of his works, including the ones from his childhood, theatre, and cinematic works. In a way, it was a success. Eisenstein’s name was well-known in the Soviet Union, and visitors of the exhibition were surprised about this creative side of the legendary filmmaker.

While most of his paintings were rather chaotic and small-sized, it was always understandable what Eisenstein wanted to tell through them. Many of those tiny artworks were pieces of a puzzle that led to the creation of Battleship Potemkin and other iconic works of the Soviet filmmaker.

It was also kind of a timeline that displayed the evolution of Eisenstein’s ideas and works. Some of the motifs he used in his early days were later translated into scenes of his movies.

In later years, several other exhibitions featuring his artworks were held across the Soviet Union and after 1991, in Russia. Also, there were published books about his passion for illustrations. Many of those literary works explained how Eisenstein’s artworks are great biographical memorabilia that help understand the character and feelings of the Soviet filmmaker. Eisenstein’s illustrations became a symbolic diary that was alongside him for most of his life.

For more history content, subscribe to our YouTube channel!

Comments

Post a Comment